No products in the cart.

Origin Profile: Colombia

Colombia is the second largest producer of Arabica coffee. Quality can range from classic breakfast blend coffees to exotic and wild microlots

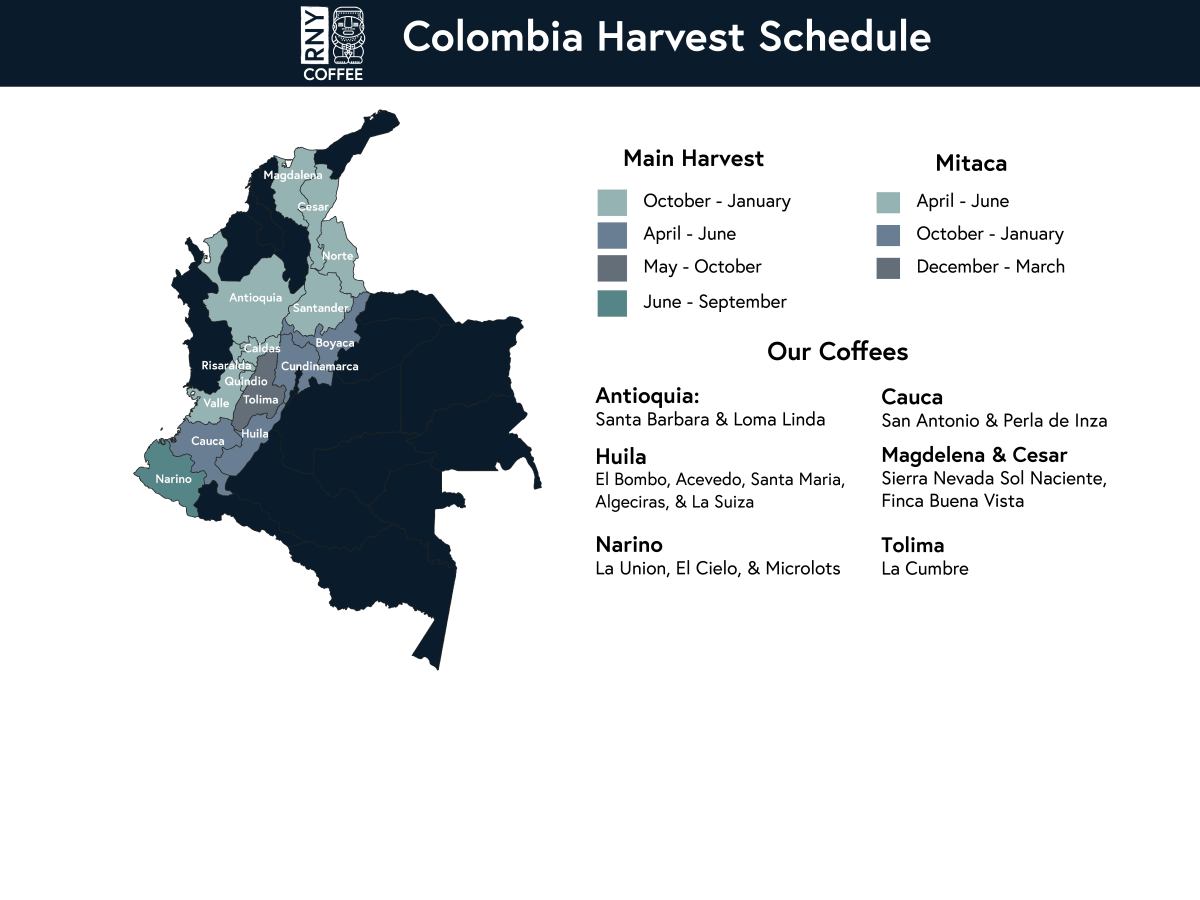

| Harvest | Varies by region |

| Arrival | January - December |

| Number of Producers | ~540,000 |

| Average Farm Size | <2 Hectares |

| Annual Production | 14.8 Million 60-Kilo Bags |

| Common Varieties | Caturra, Catuai Castillo, Typica Bourbon, Catimor |

| Grades | Supremo: >scr. 17 Excelso: < scr. 17 |

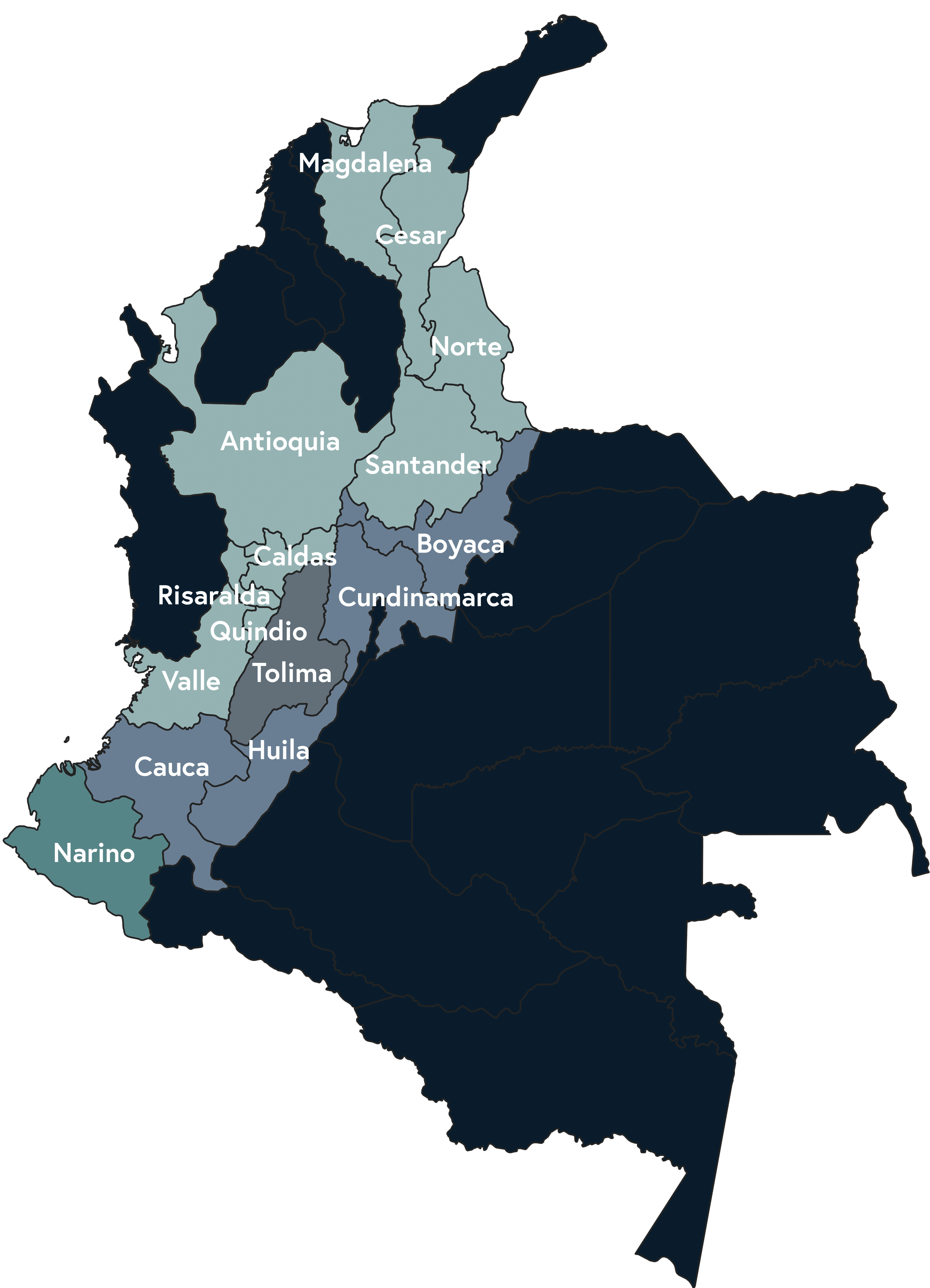

| Quindio, Risaralda, Caldas | “The Coffee Triangle” is the largest coffee producing area. The coffee is typically mild and sweet. |

| Huila, Narino, Tolima, Antioquia, Cauca | The high-mountain farms in the southern regions produce some of the best coffees in the world. There are many microlots produced here as well as high quality macrolots. The flavor profile may include a multitude of fruit notes and florality with high complexity. |

| Santander, Boyaca | The growing regions in Northern Colombia are typically lower elevation. They produce a more classic washed mild flavor profile that sweet, nutty, and slightly citric |

| Data Based on MY2019/2020 | |

Colombian coffee has always been a staple for its consistent quality. Mild acidity and sweetness of the coffee produced in the central regions is perfect for House and Breakfast Blends. More recently, the coffees of southern Colombia have become more accessible and more highly desired for their complexity and exceptional cup quality.

The origin of coffee in Colombia is not completely certain, but the most common story is that coffee arrived with Jesuit priests in the 1730s. It was not until 1835, over 100 years later, that the first coffee exports were logged from the port of Cucuta. Coffee experienced large speculative expansion in the second half of the 19th century as large estates with access to international banking and credit in Santander and Cundimarca opened to profit off coffee’s relatively high international prices. The Thousand Days War and the international decline of coffee prices at the beginning of the next century proved that this style of coffee production was unsustainable for Colombia. The estates in Santander fell into financial crises and growth of estates in Antioquia and Caldas stalled. Coffee remained a viable option for smaller farmers. It represented a more intensive farming option that could be cultivated year-round, much better than the slash and burn farming of other crops. Most of Colombian producers today operate on farms less than 2 hectares or 5 acres. Only 5% of Colombian Coffee is produced on estates bigger than 5 hectares or 12 acres.

In order to compete more effectively, Colombian Farmers formed the Colombian Coffee Growers federation (FNC) in 1927. The FNC is one of the oldest and largest agricultural NGOs in the world. The FNC’s goal is to protect the interests of Colombian Farmers domestically and internationally through collective action, education, and research. In 1938 FNC created the National Coffee Research Center – Cenicafe. Cenicafe was founded to study coffee farming including production yields, harvesting and processing methods, and resulting quality in order to improve Colombian coffee. Today, Cenicafe is proving to be successful in producing new varieties of coffee that are more resistant to Coffee Leaf Rust which will make the Colombian coffee industry more robust.

With the growth of the specialty coffee industry, Colombian coffee growers are focusing increasingly on producing high quality microlots from unique microclimates. Honey and natural processing styles are becoming more popular, especially since many growers process their coffee themselves.

The origin of coffee in Colombia is not completely certain, but the most common story is that coffee arrived with Jesuit priests in the 1730s. It was not until 1835, over 100 years later, that the first coffee exports were logged from the port of Cucuta. Coffee experienced large speculative expansion in the second half of the 19th century as large estates with access to international banking and credit in Santander and Cundimarca opened to profit off coffee’s relatively high international prices. The Thousand Days War and the international decline of coffee prices at the beginning of the next century proved that this style of coffee production was unsustainable for Colombia. The estates in Santander fell into financial crises and growth of estates in Antioquia and Caldas stalled. Coffee remained a viable option for smaller farmers. It represented a more intensive farming option that could be cultivated year-round, much better than the slash and burn farming of other crops. Most of Colombian producers today operate on farms less than 2 hectares or 5 acres. Only 5% of Colombian Coffee is produced on estates bigger than 5 hectares or 12 acres.

In order to compete more effectively, Colombian Farmers formed the Colombian Coffee Growers federation (FNC) in 1927. The FNC is one of the oldest and largest agricultural NGOs in the world. The FNC’s goal is to protect the interests of Colombian Farmers domestically and internationally through collective action, education, and research. In 1938 FNC created the National Coffee Research Center – Cenicafe. Cenicafe was founded to study coffee farming including production yields, harvesting and processing methods, and resulting quality in order to improve Colombian coffee. Today, Cenicafe is proving to be successful in producing new varieties of coffee that are more resistant to Coffee Leaf Rust which will make the Colombian coffee industry more robust.

With the growth of the specialty coffee industry, Colombian coffee growers are focusing increasingly on producing high quality microlots from unique microclimates. Honey and natural processing styles are becoming more popular, especially since many growers process their coffee themselves.